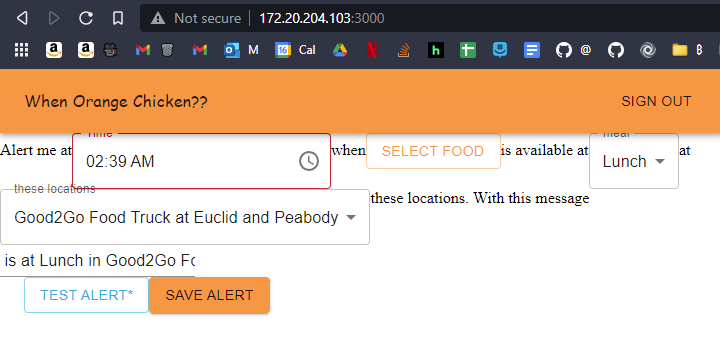

When Orange Chicken

Published: October 24, 2021

A simple, innocous question. While eating dinner, some friends and I were discussing the best Ike meals, eventually arriving at when is orange chicken next available at one of the Dining Halls littered around campus?

Any ordinary person on campus would tell you to pull out your phone, and click on each dining hall, then search for some of that delicious chicken. But instead, I thought,

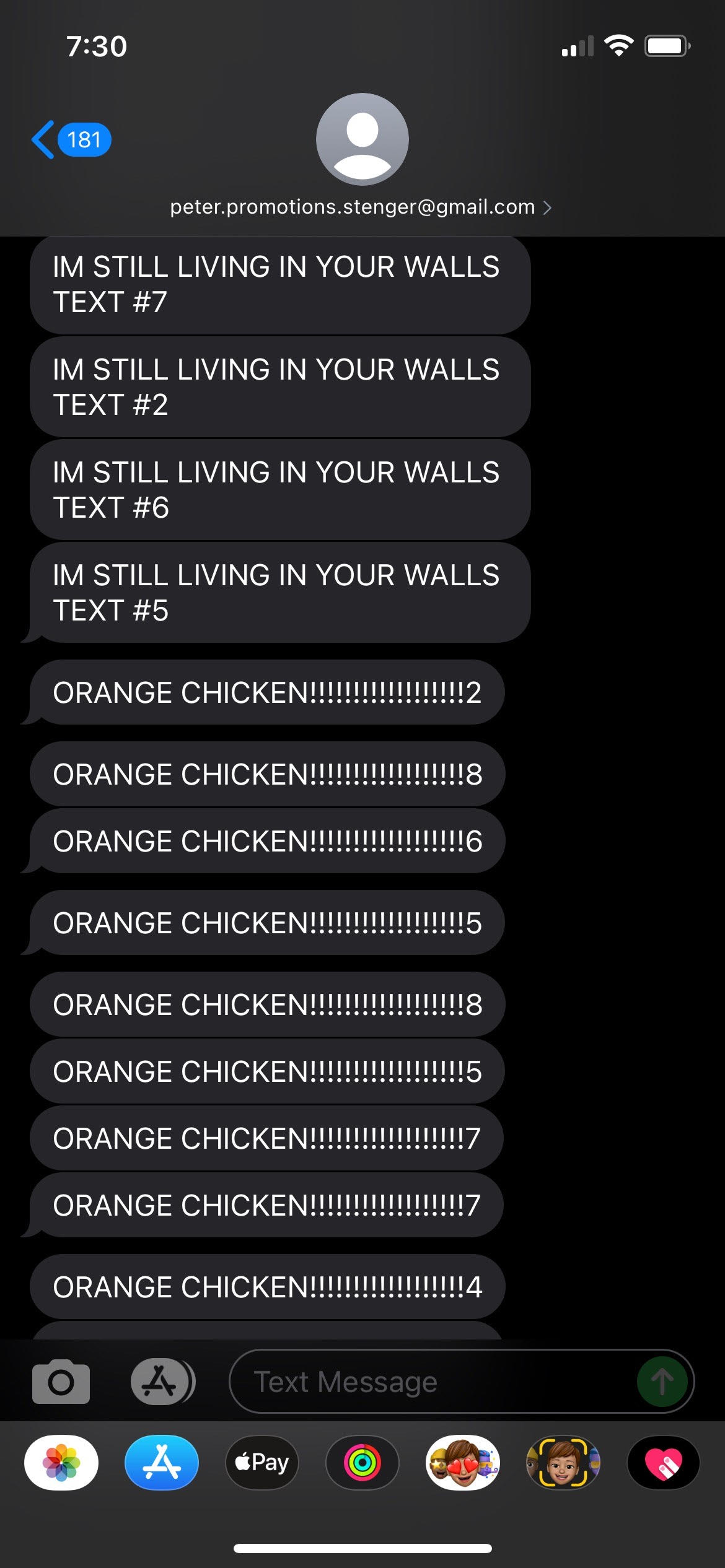

What if you received a text message every time orange chicken was available at a dining hall?.

And so that Monday evening, I started some investigative work.

Detour to the world of email SMS

The first thing I looked at was how I could even send these SMS messages for cheap (or even free!). After some searching around, it appeared that no one wanted to let me send it from a phone number for free. However, there were projects that use the carrier specific sms emails to send your message.

The most popular of these is textbelt.

In a nutshell, we configure an email provider to send email from, and then the library will send out our message as an email to a preconfigured list of email addresses where %s is the phone number you want a message to:

us: [

'%s@email.uscc.net',

'%s@message.alltel.com',

'%s@messaging.sprintpcs.com',

'%s@mobile.celloneusa.com',

'%s@msg.telus.com',

'%s@paging.acswireless.com',

'%s@pcs.rogers.com',

'%s@qwestmp.com',

'%s@sms.ntwls.net',

'%s@tmomail.net',

'%s@txt.att.net',

'%s@txt.windmobile.ca',

'%s@vtext.com',

'%s@text.republicwireless.com',

'%s@msg.fi.google.com',

// '%s@message.ting.com', // Duplicate of Sprint

// '%s@sms.edgewireless.com', // slow

],After some playing around, I was successfully sending texts!

Unfortunately, this method has some drawbacks:

1) You are sending from an email, which looks really suspicious 2) You are sending an email to ~20 carriers, when only one will get delivered. 3) This doesn’t scale well

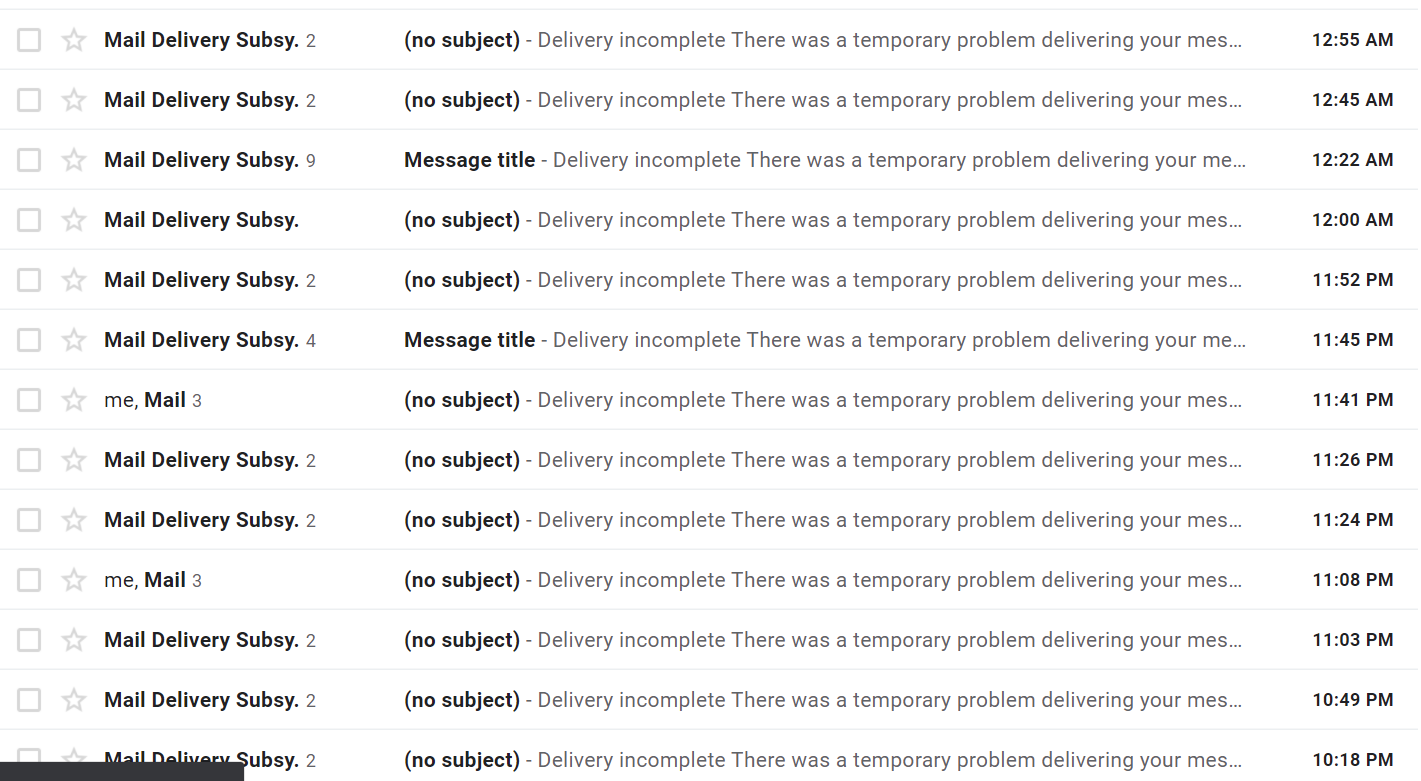

When I setup the email service, the easiest method was to connect my gmail account and use that as the SMS sender. I have since regretted that decision, as the 19/20 emails repeatedly bounce.

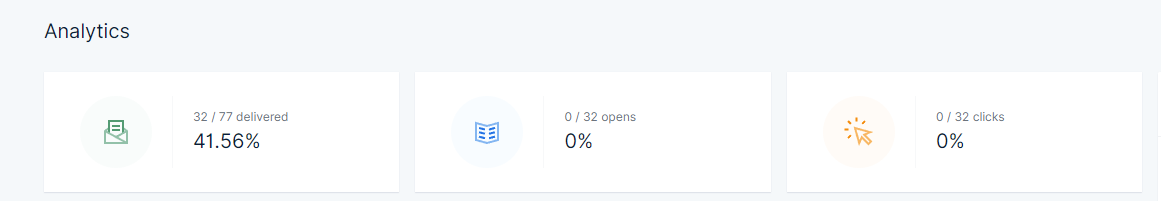

I later switched to mailgun, but I was not able to get the texts, even though the emails sent. I concluded that there must be some security protection against this sort of SMS spam

- This claim requires further research, and I had already spent an hour trying to get it to work, and so I moved onto more interesting parts of this project to determine it’s feasibility.

Playing around with web APIs

I then pivoted my attention towards the dining halls.

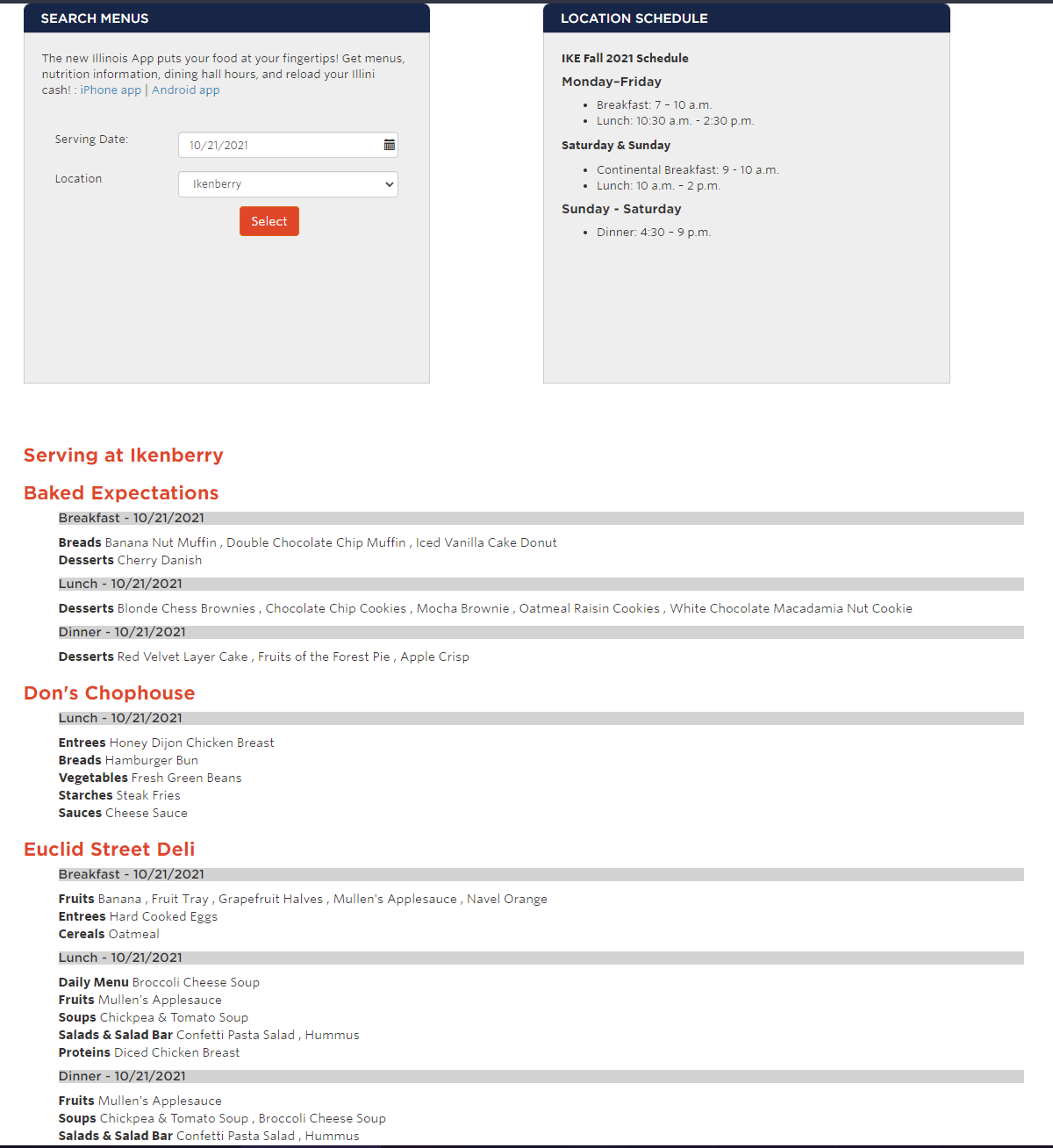

The first spot I checked was the dining hall information page. Nothing special, but it could get the job done.

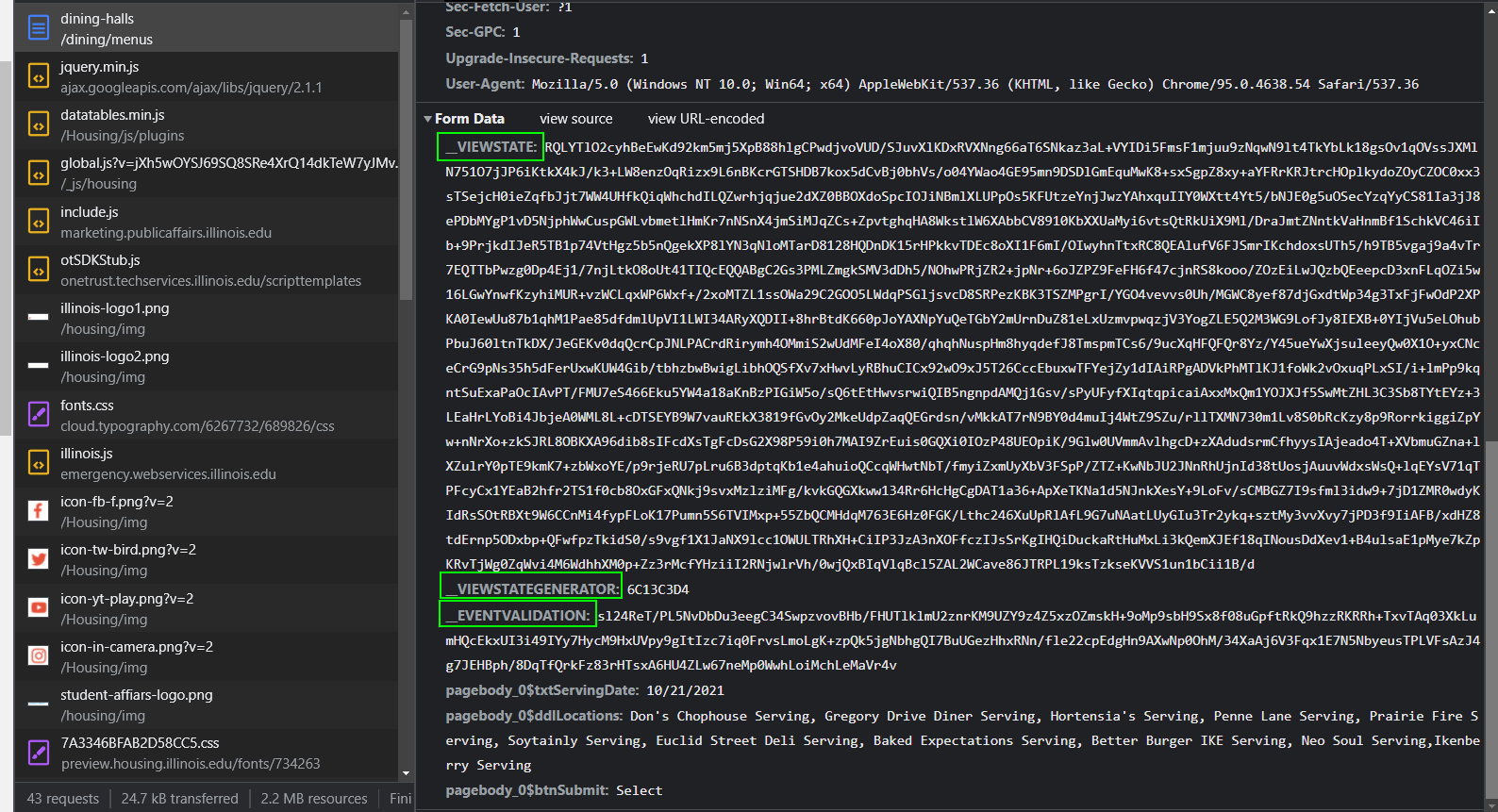

Unfortunately, after looking at the requests, we figure out that this is a .NET application and it doesn’t use any APIs.

__VIEWSTATE.

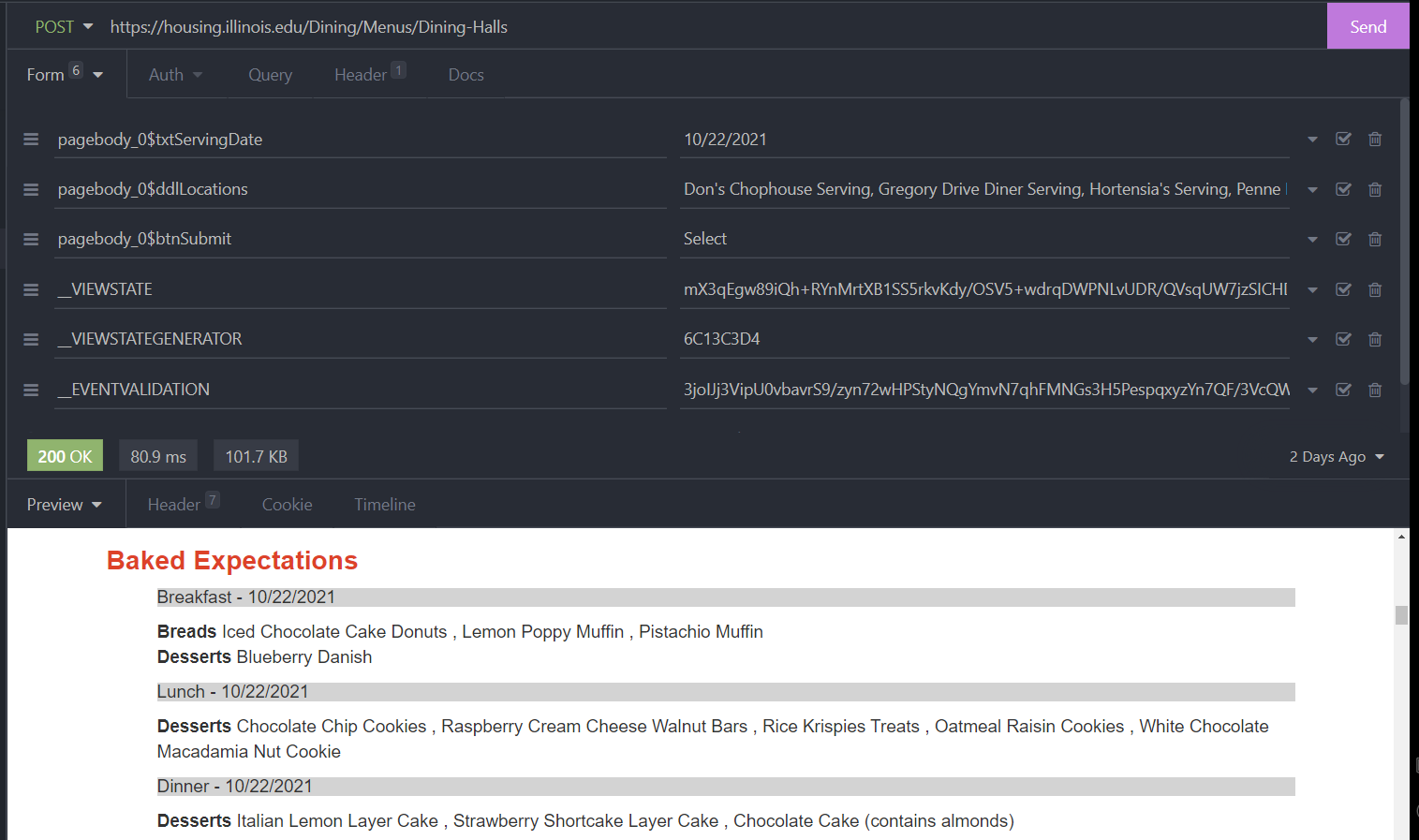

I was able to easily replicate this request in Insomnia, my favorite web request tester, showing the possibility of acquiring the data ahead of time.

I could have stopped here, and created a python script running to screen-scrape the menu and then send out emails. But would I be a true software engineer if I did that?

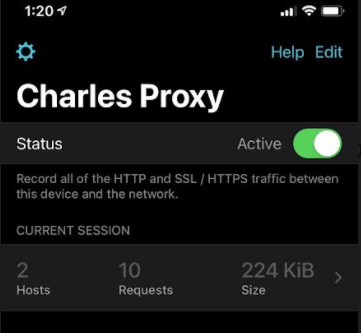

The Illinois Dining App

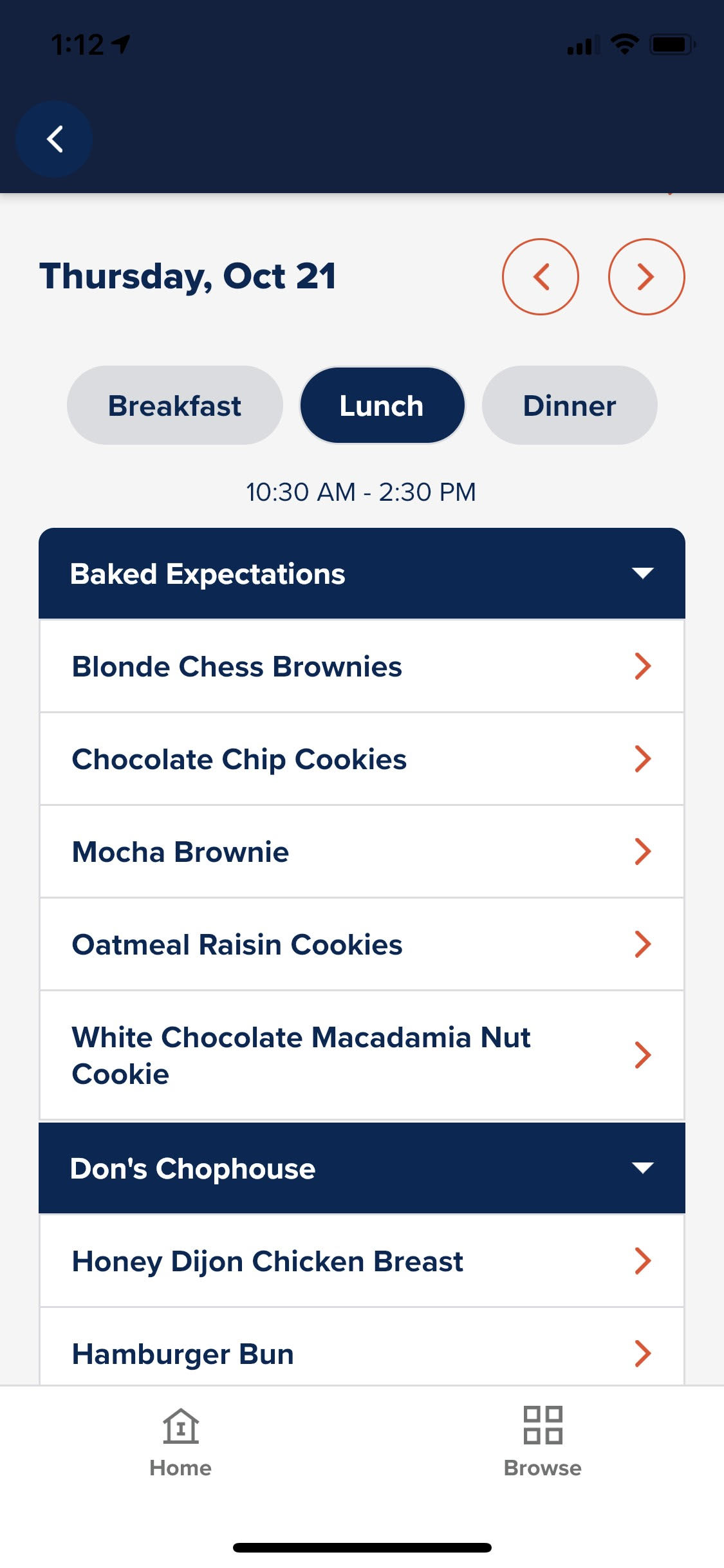

Most people at Illinois are familiar with the Illinois App: It shows you the locations and menu for all the dining halls. The app’s information comes from somewhere, and that place is 99% of the time an API.

Reverse-engineering closed-source APIs is pretty much my specialty, and I really enjoy doing it. I’ve done it lets see, one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine times and turned it into an open-source library. DATA EQUITY FTW!!

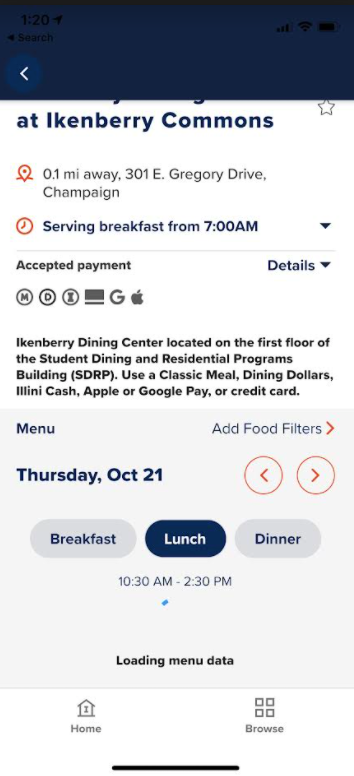

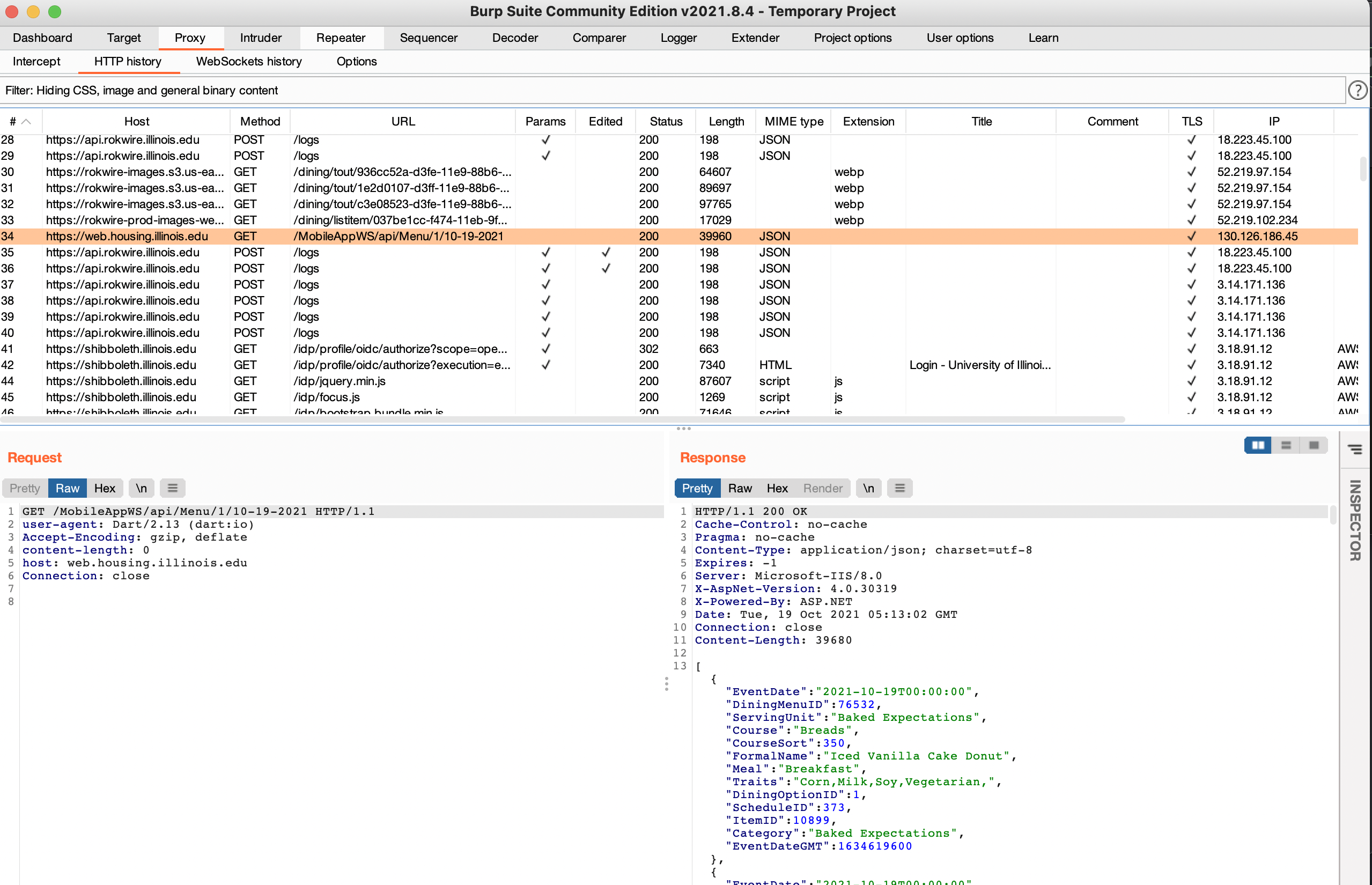

Enter Charles.

A MITM (Man-in-the-middle) proxy for intercepting mobile requests. In the best case scenario, I can inspect the requests directly from Charles with no further work.

However, once we start intercepting requests, we see the spinner of death :(

Pair the spinner with a suspiciously low number of requests made by the app, and we have a pretty strong case that SSL pinning is in place. SSL pinning is designed to protect against people like me who are trying to intercept (and possibly modify!) web traffic to a mobile app.

Pair the spinner with a suspiciously low number of requests made by the app, and we have a pretty strong case that SSL pinning is in place. SSL pinning is designed to protect against people like me who are trying to intercept (and possibly modify!) web traffic to a mobile app.

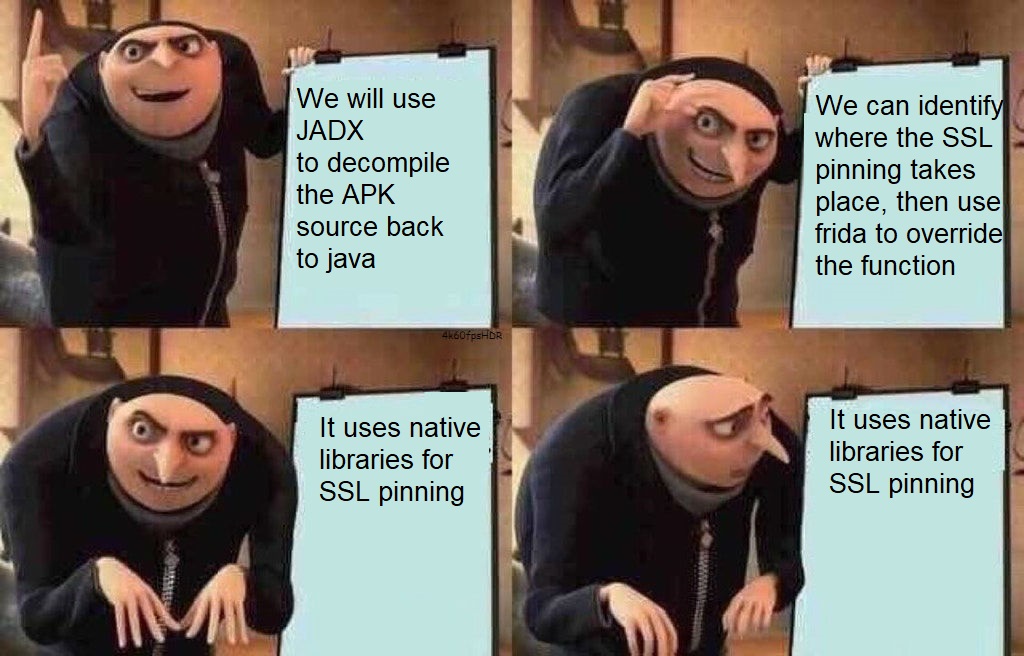

Luckily, two weeks ago, I did a deep dive into bypassing SSL Pinning on Snapchat. I won’t go into detail of how to perform the same steps I did, but this blog by HTTP Toolkit does a great job explaining how it can be bypassed.

In order,

- Acquire Android Emulator w/ rooted android phone & install Frida

- Install Burp Suite to monitor requests

- Proxy requests you make on the emulator through burp suite to monitor traffic

- Use the ~magic~ of Frida to bypass SSL pinning

- Profit!!

Completing steps 1-3, I was able to confirm my hunch in the adb logcat output: SSL Pinning is stopping us from viewing what web pages it views.

adb logcat output

This output pretty clearly shows us that native libraries are involved in SSL pinning.

Time to bring out the heavy artillery

After decompiling the source using APKtool, we can identify that this application is actually written in Dart/Flutter (a fairly new mobile app programming language/platform for those not family).

After reading more into how the Dart VM works, I figured out that most of the business logic happens inside the shared object file libapp.so. This is a beast of a file: I am not interested in reverse-engineering a VM (a well-known obfuscation technique)

Since Flutter is such a new language, reverse-engineering support is sparse: Doldrums seems to be our best bet, but our app version is too new for it to work :(

Luckily, we aren’t the only person to attempt dart SSL bypassing:

These 4 articles greatly helped me get it working.

- https://nachiketrathod.com/Intercepting-Flutter-Android-Application/

- https://medium.com/@ryanfabella/bypass-ssl-pinning-flutter-didevice-x86-64-avd-d319343b0039

- https://id.horangi.com/blog/bypass-ssl-pinning-di-flutter-library/

- https://blog.nviso.eu/2020/05/20/intercepting-flutter-traffic-on-android-x64/

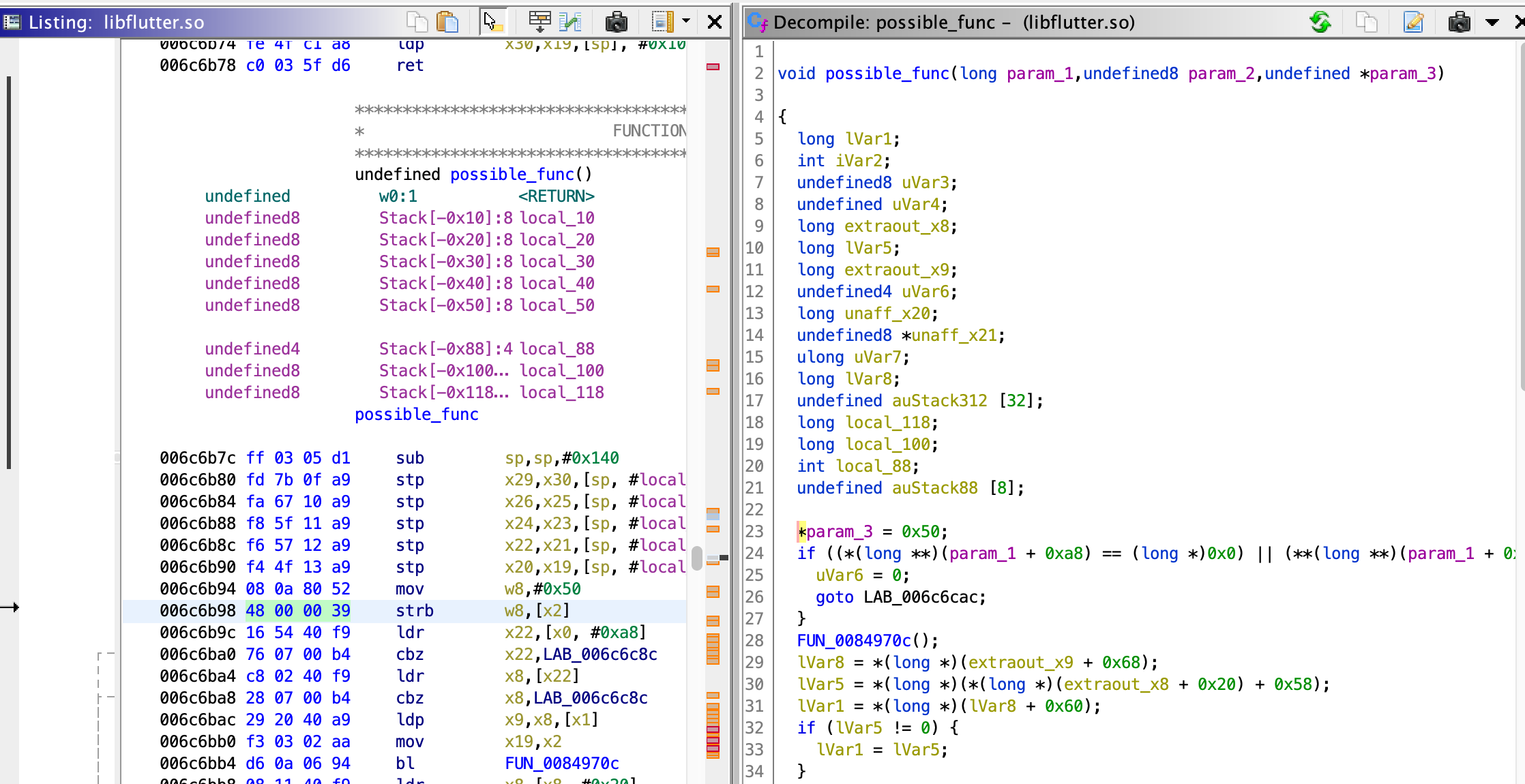

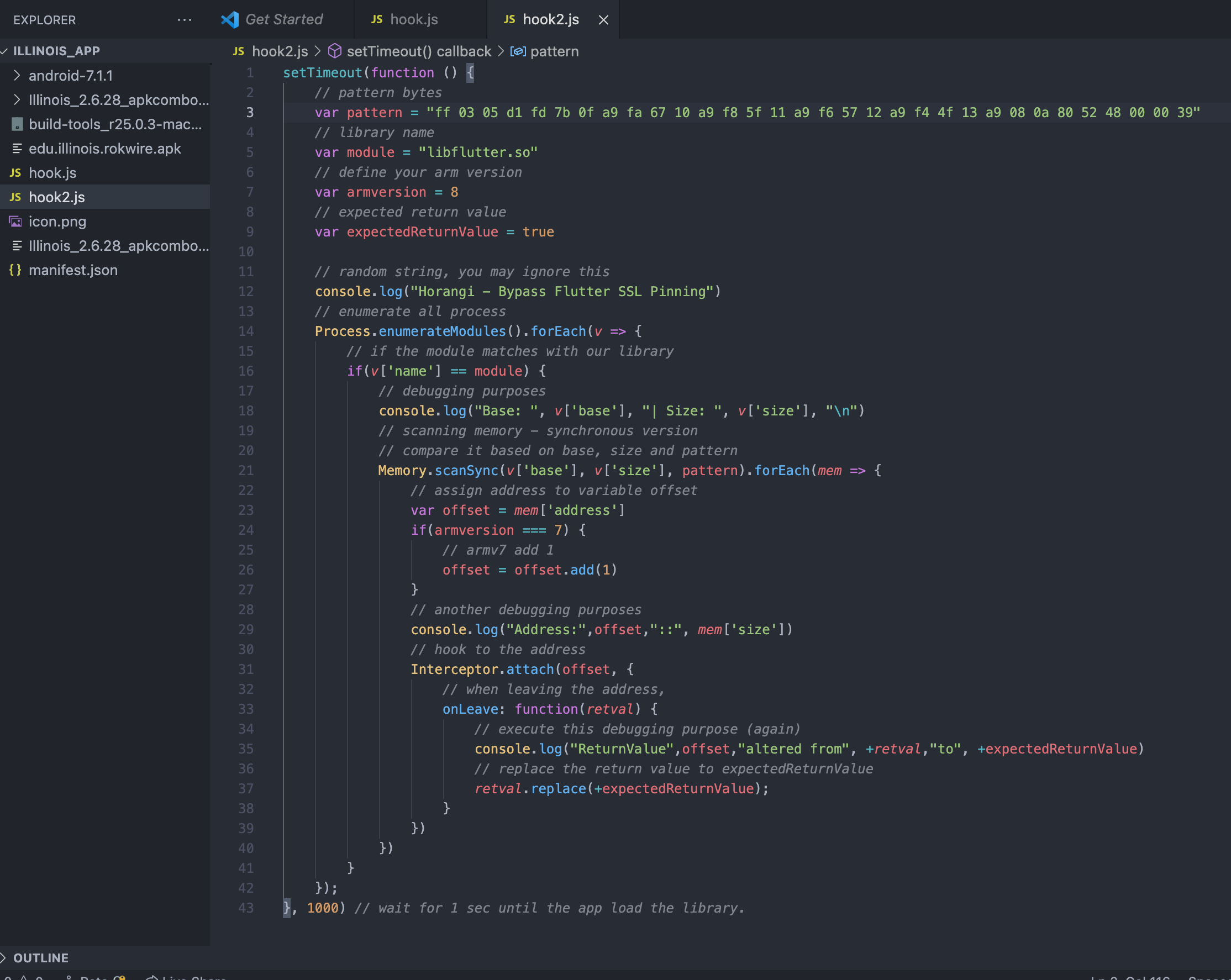

First, I tracked down the function in my version of flutter:

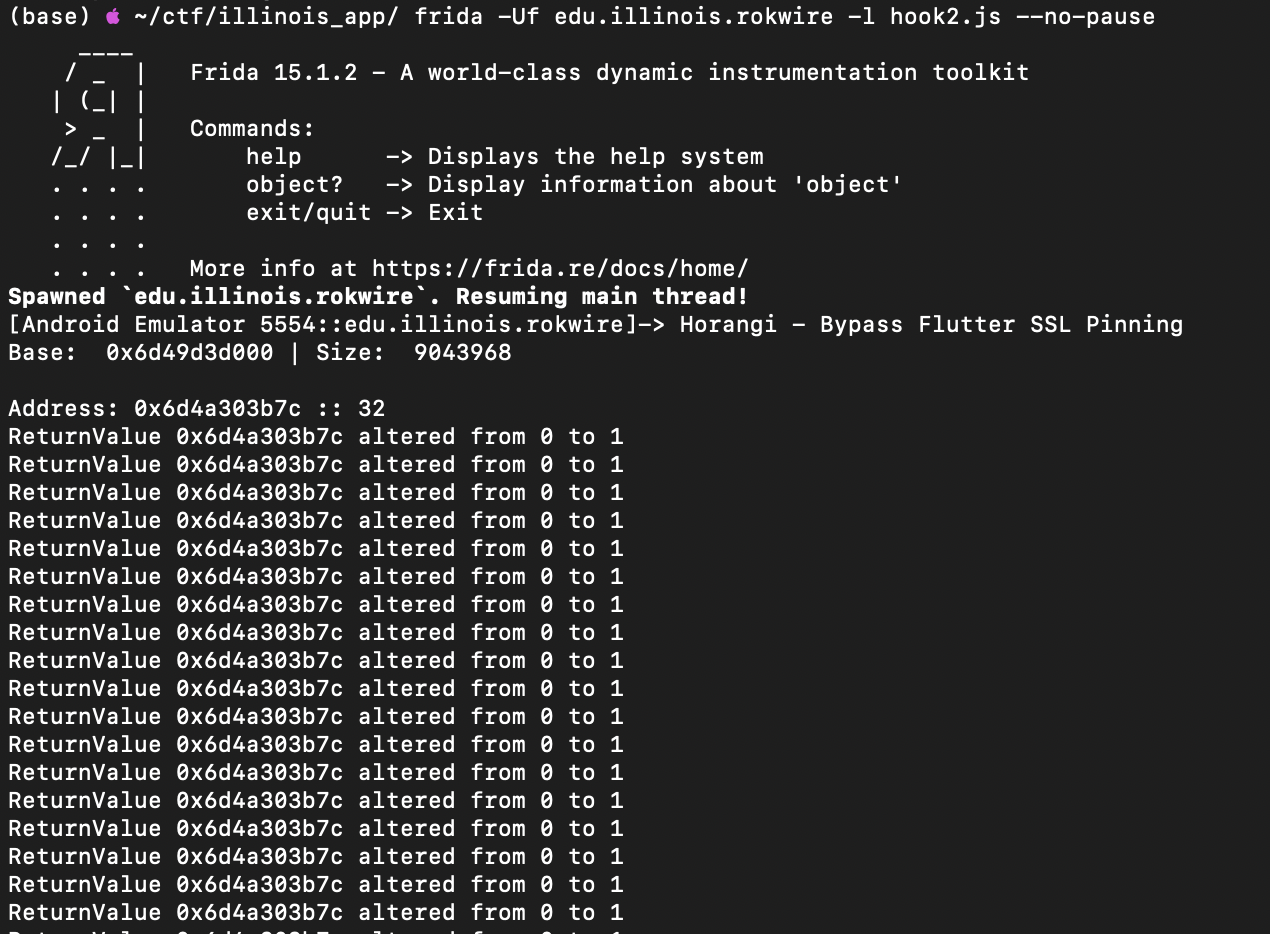

This was my final exploit, a modified version of the Horangi script.

And we are rewarded with some sweet sweet burp logs!

And find… unauthenticated mobile API endpoints

And find… unauthenticated mobile API endpoints

A nice prize after so much work :)

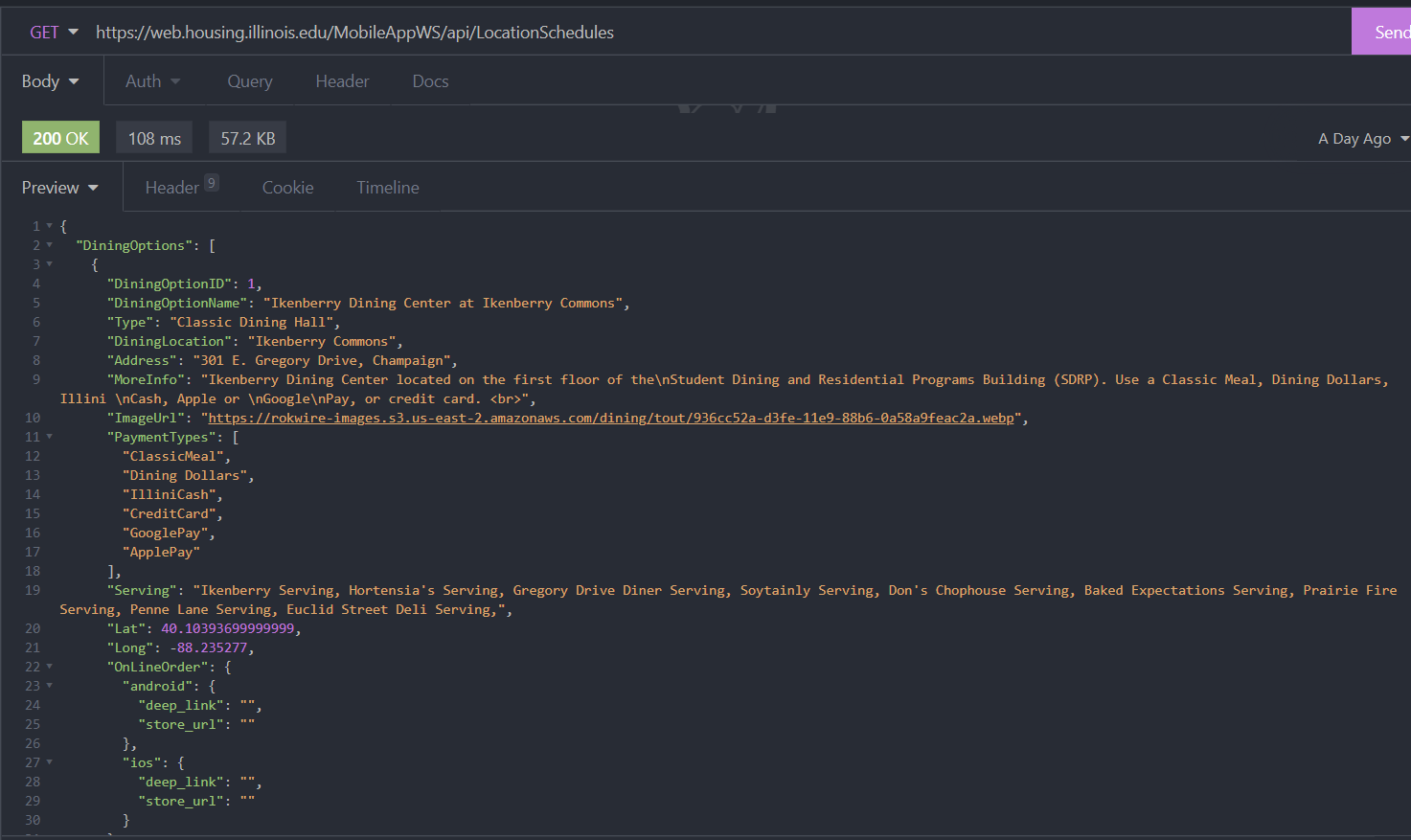

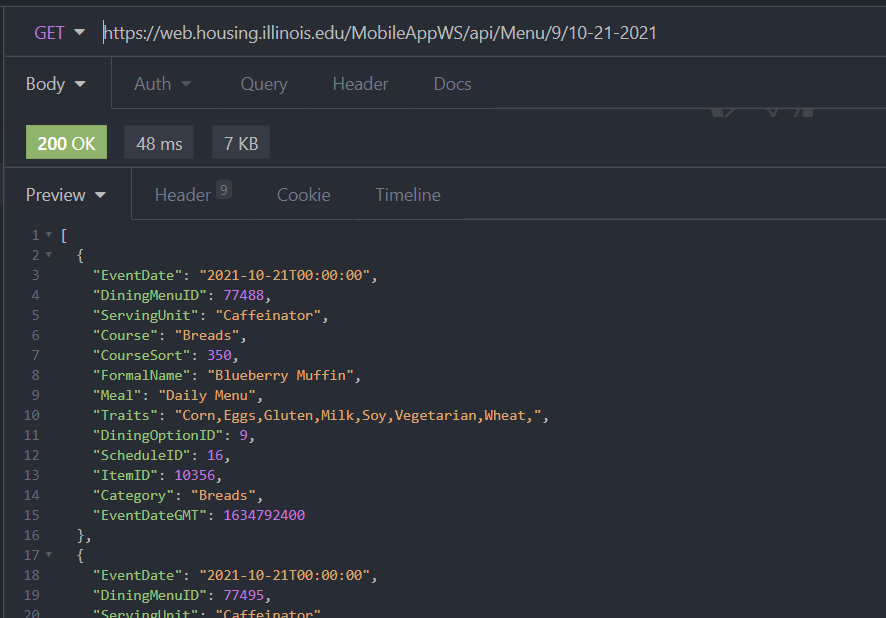

Mirroring these requests using Insomnia, we find two endpoints we care about:

The list of locations,

https://web.housing.illinois.edu/MobileAppWS/api/LocationSchedules

As well as the menu for that location on a certain day:

https://web.housing.illinois.edu/MobileAppWS/api/Menu/<diningID>/<date>

Technology Stack and Planning

After this point, I decided that I wanted to turn this project into a full webapp. After some careful consideration, I ended up with a tech stack:

| Service | Used | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| SMS Messaging | Twilio | Cheapest rates for actual SMS |

| Database | Firebase | I wanted to try a new technology for this project |

| Front-End | React + Next.JS + MaterialUI | Familiar with React, wanted to try SSR (Next.JS) |

| Hosting | Firebase hosting | Try it out |

I also made some other decisions: Obviously this webapp would be able to do more than just Orange Chicken, will provide some needed customization, and I will try to store all the data I will need in Firestore, and use Cloud Functions for other tasks, like sending messages and fetching the menu for the day.

Authentication

Authentication scares me, so I always do it first. I didn’t really implement anything special, so I will just overview what I resarched instead. I looked into types of Illinois authentication, which boiled down to shibboleth, OpenID Connect, and Google.

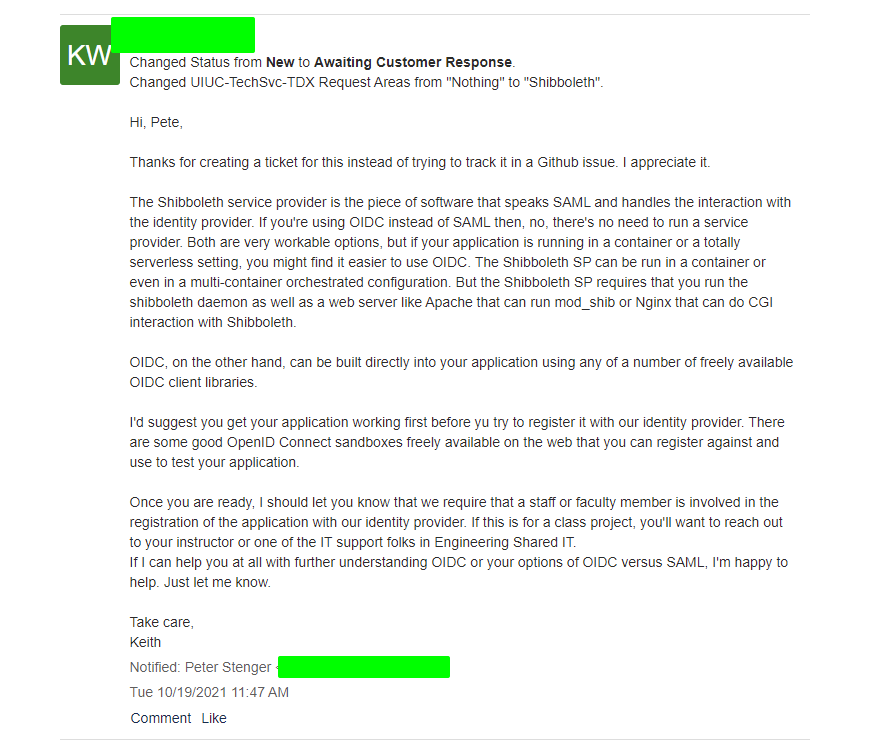

I don’t think any explanation I make of the first two is going to be better than the official Illinois tech support guy, so:

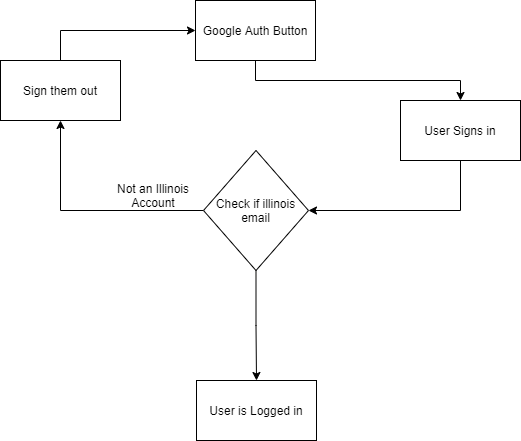

I decided to go with authentication method #3 because:

1) shibboleth authentication sounded hard to setup, and would require me to self-host something (I couldn’t just use Firebase hosting) 2) I would need to build out the application first, before asking to register with OpenID Connect. [edit] Now that it is built, I could reach out… 3) Google Auth is built-in to firebase authentication, making it very easy

tldr; I am lazy

Development Process

I forgot to take screenshots of the development process, sorry about that! If you want to see a more detailed view of the development process, please just view the commit history of my github repo :)

Initial Baby Steps

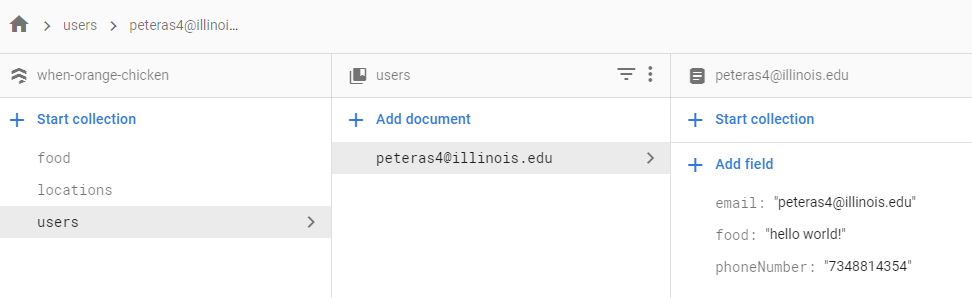

As I said, I first implemented authentication. I then pushed the user to the Cloud Firestore database. Firestore is a NoSQL database, which means that there are no ForeignKeys or SQL-style querying allowed. Overall, I am happy with how much I learned and what I ended up with but it was confusing at times.

Filling in the database

I then setup a cloud function to pull down data from the API every day at 1AM and into the database.

export const updateMenu = functions.pubsub.schedule('0 1 * * *')

.onRun(async context => {

const d = new Date();

const today: string = d.toLocaleDateString().replace(///g, "-");

const meals = await getFoodForDay(today);

const items: Promise<any>[] = []

for (let [mealTime, mealTimeEntries] of Object.entries(meals)) {

db.collection(`food/${today}/meals`).doc(mealTime).set({

name: mealTime

})

for (let [item, value] of Object.entries(mealTimeEntries)) {

items.push(db.collection(`food/${today}/meals/${mealTime}/items`).doc(item).set(value as FirebaseFirestore.DocumentData))

}

}

console.log(`Waiting for ${items.length} Items `)

await Promise.all(items);

})UI Madness

Most of the UI development process went smoothly, I always forget how to use MaterialUI and so it takes me 2x as long to do basic things, like make a react button. I ended up using styled-components, which made styling things way easier:

Most of the UI development process went smoothly, I always forget how to use MaterialUI and so it takes me 2x as long to do basic things, like make a react button. I ended up using styled-components, which made styling things way easier:

styled(Container)`

display: flex;

flex-direction: row;

justify-content: space-apart;

`

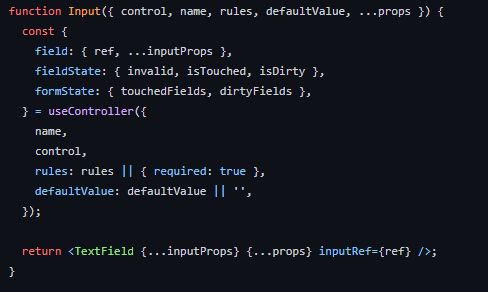

React is great for most things, but what it is not known for is forms. This may have been the most infuriating two hours of my life to validate a phone number. The only advice I have to you is that while useState hooks can be annoying, integrating react-hook-form into a UI library is worse.

Re-engineering

As I built out the site more, I realized I would have to redo my original data structure:

root

- users

- food

- breakfast

- (DATE)

- food item 1

- lunch

- (DATE)

- food item 2

- dinner

- (DATE)

- food item 3The main issue I was facing was in the UI, there was no easy way to display all food elements without performing a metric ton of queries.

After opening a couple tabs,

, the limits of firestore querying finally drove me to StackOverflow, where I got answered by this absolute legend:

, the limits of firestore querying finally drove me to StackOverflow, where I got answered by this absolute legend:

He gave me a pretty crazy looking path structure to use,

/food/{date_doc}/meals/{meal_doc}/items/{item_doc}

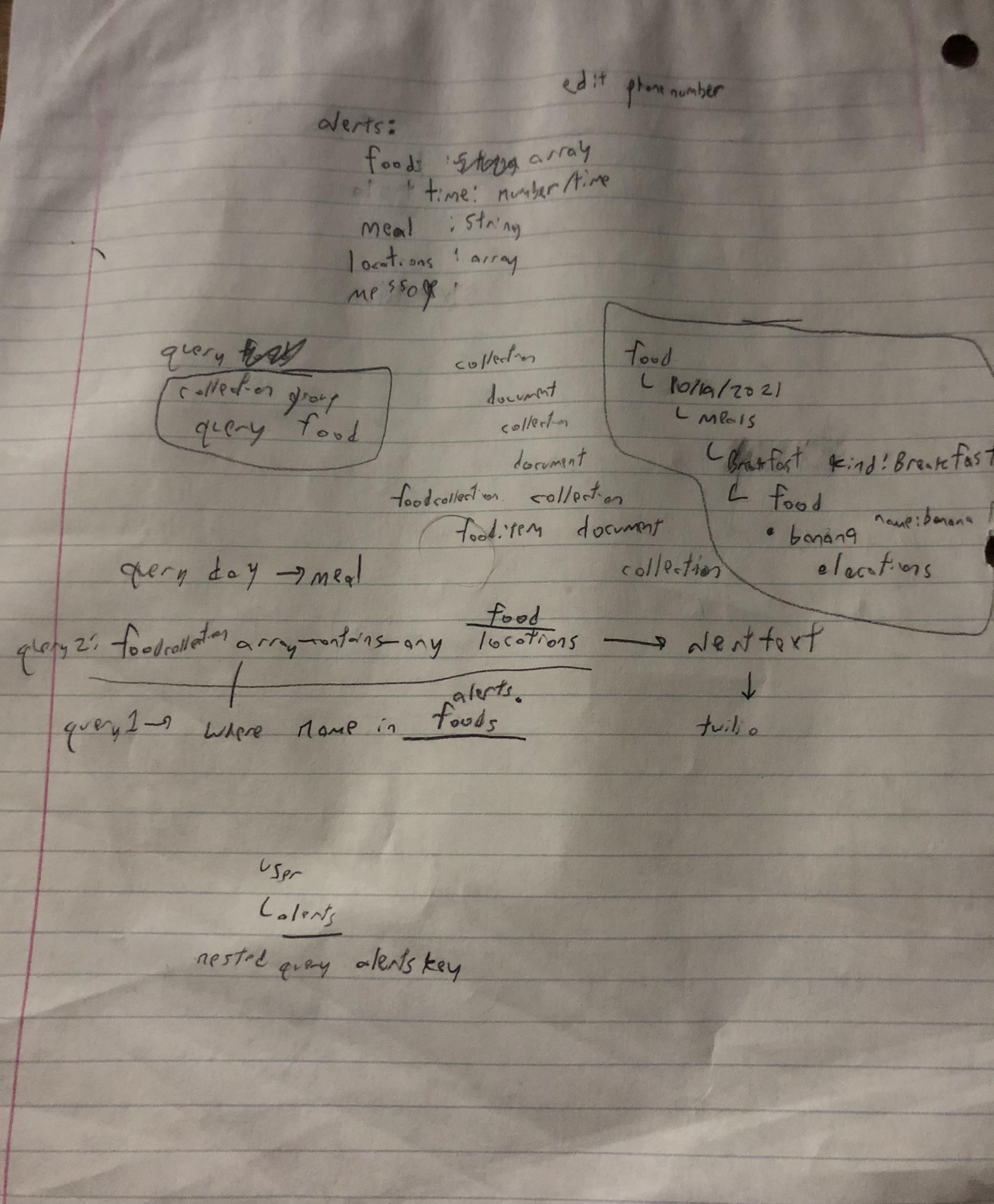

, but after thinking it out on paper, I figured out a data structure for the food elements, as well how to query for food in this structure based on my alerts.

Final Strides

By Wednesday evening, I had already spent a ton of time on the project and wanted to finish it up soon.